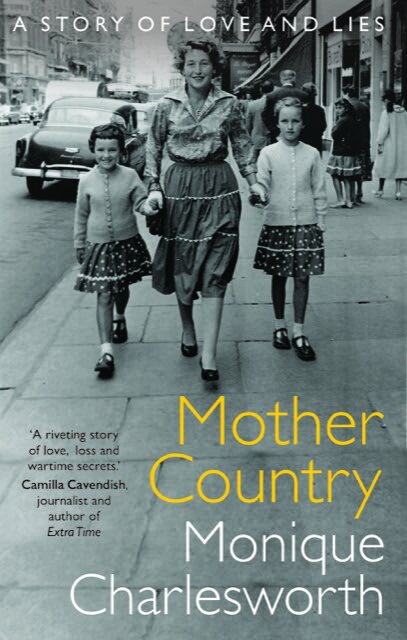

A fascinating new memoir Mother Country : a story of love and lies by Monique Charlesworth describes her late mother’s extraordinary life and story growing up as half Jewish in thirties Germany and her subsequent journeying around Europe surviving and trying to fit in.

Damaged by a youth of persecution, exile and loss of education, Inge constantly reinvented herself, refusing ever to see herself as a victim.

Growing up with such a parent was clearly complicated as Inge hid information as a matter of course. By the time she was in her 90s, she was living in France and for decades had successfully concealed who she really was - her French friends thought she was an Englishwoman and had no idea that her life had been so painful.

But her daughters knew that she was really German. And Inge knew that they could expose her, if they so chose.

She in turn chose to keep deep secrets of her own from her two girls.

The result was constant mutual tension and irritation; Inge claimed to long for visits from her family, but she also made sure that they were swiftly curtailed.

This particular excerpt (describing a visit to France in Inge’s old age) resonated: Monique describes how even a simple matter such as making lunch took was imbued with unexpressed tensions.

“Lunch was Inge’s main meal (usually her only meal). We always had fish because I am the expert who supposedly knows how to cook it. I would buy the fish plus a lemon, fearing the furry fridge one. Then I would make the mistake of squeezing lemon over the grilled fish. At once, Inge would push her plate away in disgust.

‘Water everywhere. It’s probably not cooked through. Nobody could eat that.’ She was hungry, but it gave her more pleasure to leave the fish than to eat it. That way she won. So I’d mop up the juice with kitchen paper.

‘It’s cold. I can’t eat cold food.’

I’d put the plate in the oven. When it reappeared, it was worse.

‘It’s dry. Overcooked.’

The piece of foil I’d used was wrong – it was never clear how. Too large? Too small? The wrong way up? By now, her hands would be trembling with rage.”

Both women were angry - and neither could speak openly.

Monique’s question was this : - how should I have behaved? Was there a way to defuse the situation.

What a shame for you that your visit would always create such tension and build strong emotions when you were being kindly and wanting to be loving. It must seem astonishing that you felt unable to open up a dialogue, never mind challenge your mother over these episodes. There are probably many reasons why this was the case.

Perhaps you learnt early on that some areas were too dangerous to question. Maybe you felt the need to soothe your mother and acquiesce to her at times unreasonable demands. Did you find yourself seeking her approval and perhaps afraid of an angry outburst? Might you have avoided further pain for her by quietly accepting the contradictions and illogical comments?

When talk becomes a more irrational it becomes very frightening to hear, even when we are adults. Often we are really scared of rejection, or worse abandonment, and this can be terrifying. Some people find that such fears can still be triggered even when their parents are no longer alive - the aftermath remains traumatic.

Of course when feelings are running so high and the criticism swings from one point to another in an endless irrational stream it is not possible to have a calm discussion. The problem for those with really difficult parents is that sadly there is never a time when that reasonable talk can happen. Such parents will find a myriad ways to avoid, deny and reject the need for a resolution.

So what can be done?

It is important to recognise that whatever the circumstances and origins of your difficult parents and their behaviour, they will never change.

But you, the child, could do things differently. There are three main options. Firstly if the criticism and behaviour is too endless, extreme and unbearable you could completely remove yourself from the relationship. But this level of estrangement can feel extreme and so is not acceptable to everyone.

Deciding to keep a distance and visit or contact message only occasionally is a step back that might help some. When you do visit you can set some boundaries, such as walking out of the room or ringing off when your parent is rude or offensive.

Finally you could continue to visit but try to change your expectations and behaviour.

Imagine that you are your parents’s carer and therefore have a more professional relationship. You can still set boundaries and step away if they are unpleasant, but in that role you would find that you can be more objective and distant. In this role it is may easier not to take the comments personally and feel so hurt.

It is so sad that you were not able to have the authentic relationship that you would have loved with your mother. One where you both felt safe to share your experiences and trust that you would each be heard and understood.

Mother Country: a story of love and lies is published by Moth Books on March 2, 2023